For centuries, yoga has been described as the union of body, mind, and soul. From this definition, we can understand much about yoga asanas by focusing first on the “body” the primary tool in any asana practice.

On the physical level, an asana involves specific movements and postures that stretch and strengthen the body, improve flexibility, support healing, and enhance overall well-being.

Yet the meaning of yoga asanas goes far beyond the physical.

The body is just a tool used in asanas, and the tools are always used to achieve something big we can’t do by normal means.

Through steady, mindful practice, asanas help still the body so the mind can also find balance and calm.

Jump to Section

- What is Yoga Asana?

- Yoga Poses Classification [infographic]

- History of Yoga Poses

- Origin of Yoga Poses

- How Many Yoga Asanas Are There?

- Why 84 Asanas?

- Benefits of Yoga Poses

What is yoga asana?

The Sanskrit word asana comes from the root term asi, meaning “to be” or “to sit.” In its simplest sense, an asana is a seat, pose, or posture whether sitting, standing, twisting, or bending. However, not every posture is considered a yoga asana.

A yoga asana is a specific physical posture practised with full awareness. It requires engaging certain parts of the body while directing the mind’s focus entirely into the pose.

In yoga, awareness is the essence of the practice without it, the movement is just exercise.

Yoga asana & raja yoga

In Patanjali’s Raja Yoga, asana is the third stage of the Eight Limbs of Yoga; a progressive path that leads to samadhi (the state of pure bliss). The sequence is:

- Yama (Social Ethics)

- Niyama (Observances)

- Asana (Physical Posture)

- Pranayama (Breathing techniques)

- Pratyahara (Turning Inward)

- Dharana (Concentration)

- Dhyan (Meditation)

- Samadhi (Pure Bliss)

According to Patanjali, an asana is primarily a stable, comfortable seat (such as Padmasana or Sukhasana) that supports prolonged meditation. It is the balance point between effort and ease steady yet relaxed.

In Hatha Yoga, however, the approach differs slightly. Before practising asanas, one is encouraged to first perform Shatkarma (six body purification techniques) to prepare the body and mind.

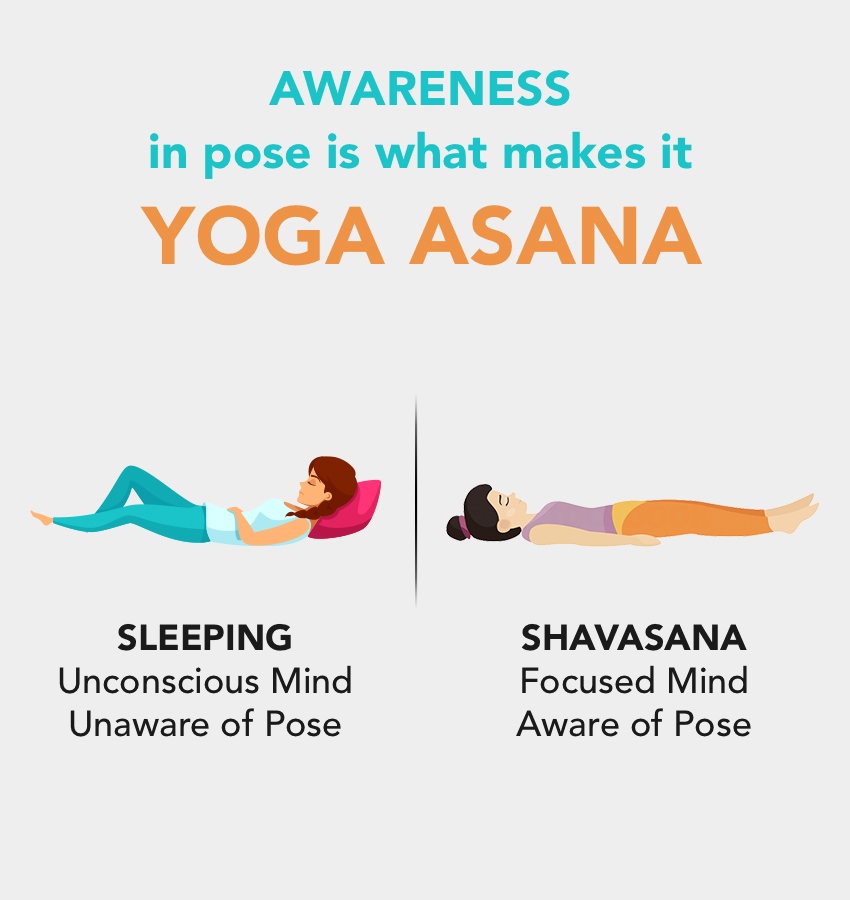

Yoga asana vs basic body position

Have you ever noticed your posture when you’re simply standing, sitting, or lying in bed? Most of the time, probably not.

In contrast, when you are in a yoga pose, there is a conscious awareness of being in that posture.

Take the example of lying down while sleeping versus lying in Shavasana. Physically, the body may look similar in both situations. But after an intense yoga session, when you rest in Shavasana, your breathing pattern, mental state, and overall experience are completely different from those during sleep.

The reason is simple: in a yoga asana, the body and mind are engaged with full awareness. You consciously sense your entire body even its subtlest movements. When the mind is wholly aware of the body, it leaves no space for wandering thoughts. This is the inner mechanism at work in every yoga asana.

How asana efforts are no longer efforts

In the beginning, every yoga asana requires conscious effort both to enter the pose and to remain fully present in it. This initial effort is important because it draws the mind’s attention to a single point: the posture itself, rather than allowing it to wander.

For example, compare simply sitting on a chair with practising Utkatasana (Chair Pose).

When performing chair pose, you:

- Bend the knees

- Bring the thighs parallel to the ground

- Hold the position for a period of time

The purpose of this effort is not to achieve a perfect image of the pose stored in your mind, but to engage the body in such a way that it naturally calls the mind to focus. As your knees and thighs feel the work being done, your attention instinctively settles on that sensation.

This focused awareness becomes the bridge between body and mind. Once the mind is fully absorbed in the posture feeling and observing without distraction the physical effort no longer feels like effort. The asana transforms into a steady, easeful state, as described in the yogic principle: Sthira Sukham Asanam a posture that is both stable and comfortable.

How yoga asanas help connect the body and mind

The inner journey through yoga asanas begins with the body, moves to the breath, and then reaches the mind. In this way, the practice connects the different energy layers of our being.

The body is the most visible expression of the pure consciousness that resides within the chitta (mind in yogic philosophy). To experience this consciousness, yoga asanas act as a physical channel, allowing energy to flow through the nadis the subtle energy pathways in the body.

When asanas are practised in harmony with pranayama (breath control), we consciously direct prana the life force into the specific form of the pose. At this stage, we begin to gain control over both body and breath, guiding the flow of energy with intention and awareness.

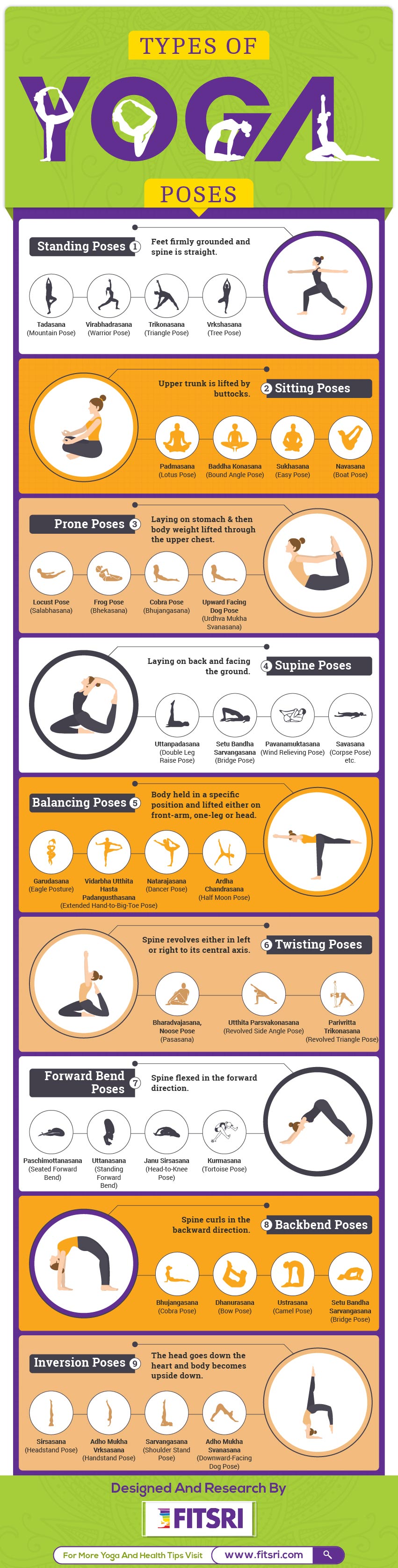

Classification of yoga poses

Yoga poses (asanas) can be grouped into different categories based on their physical movement, posture type, and energetic effects. These classifications help practitioners choose sequences that balance strength, flexibility, and inner calm.

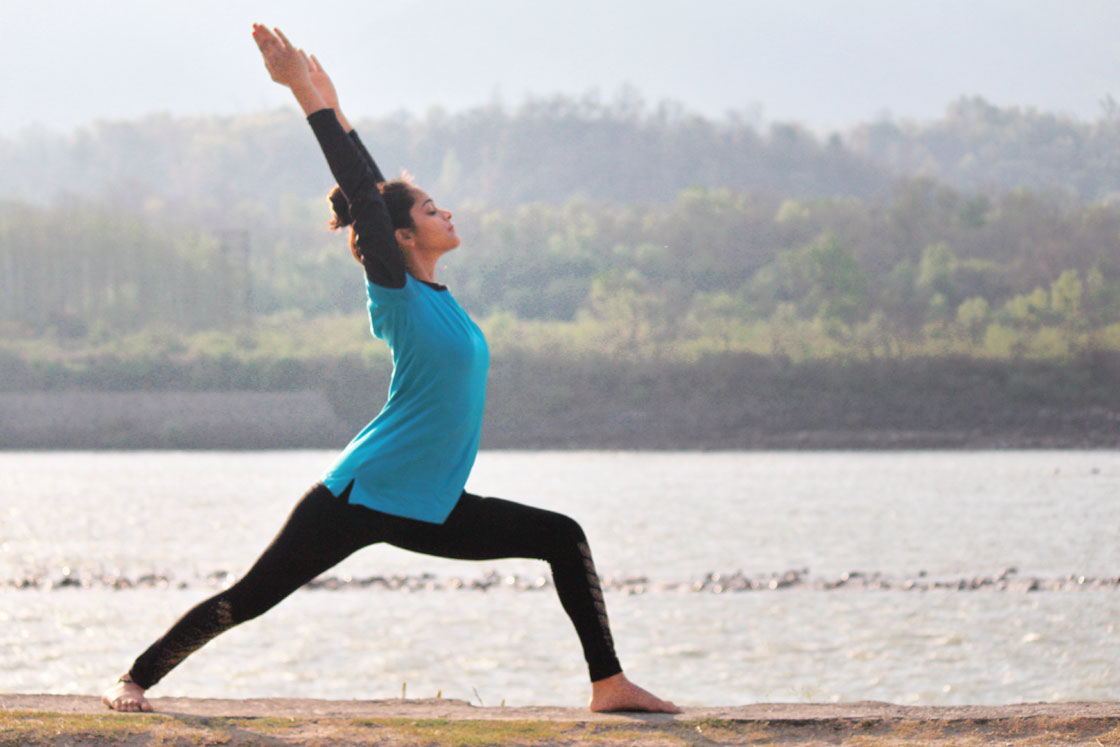

1. Standing Poses

Standing yoga poses are postures where the feet are firmly rooted to the ground and the spine is held upright. In these asanas, the strength of the lower body supports movement and alignment in the upper body. Most yoga sessions begin with the foundational standing posture Tadasana (Mountain Pose).

A strong and stable base is essential for practising forward bends, backbends, and twists effectively. Standing poses help develop this base by strengthening the feet, ankles, and legs while improving posture and balance. This is why they are often called the foundation of yoga practice.

Common Standing Poses

One-Legged Standing Poses

These are also part of balancing postures, requiring focus and coordination:

2. Sitting Poses

Sitting yoga poses are postures where the weight of the upper body is supported by the buttocks rather than the feet. These poses often form the starting point of a yoga class, as they encourage stillness and allow us to observe the body’s sensations with quiet attention.

Seated asanas are especially suited for meditation because they help maintain an erect spine, keeping the body alert and active during prolonged periods of sitting. This upright yet relaxed posture supports steady breathing and focused awareness.

Common Sitting Poses

Common Seated Meditation Poses

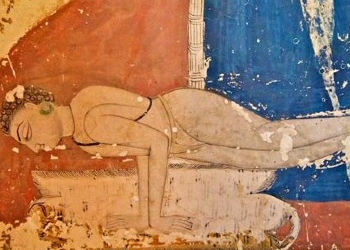

3. Prone Poses

Prone yoga poses are performed while lying on the stomach, with the body supported through the chest, abdomen, and pelvis. These are sometimes called reverse corpse poses because they are practised in the opposite position to Savasana.

Prone poses are highly effective for toning the abdominal organs, strengthening the back, and improving posture. They can also help flatten the stomach and enhance digestion. For beginners, props such as a folded blanket can be placed under the chest or forehead for support and comfort.

Common Prone Poses

4. Supine Poses

Supine yoga poses are the opposite of prone poses here, the back rests on the ground while the front of the body faces upward. These postures often require good spinal flexibility, so it’s helpful to prepare with gentle stretching before attempting them, especially at a beginner level.

Supine poses are excellent for releasing tension from the spine, calming the nervous system, and deeply relaxing the body. This is why most intense yoga sessions conclude with a supine posture such as Savasana (Corpse Pose), allowing the benefits of the practice to settle in.

Common Supine Poses

5. Balancing Poses

Balancing yoga poses are postures in which the body’s weight is held in a specific position often on the forearms, hands, or a single leg. These asanas demand a strong foundation built through preparatory poses, as well as consistent practice over time.

To maintain stability in balancing postures, both physical flexibility and mental focus are essential. A steady gaze (drishti) and controlled breathing help align the body and calm the mind, allowing the pose to be held with ease.

Balancing poses can be found in various categories, including standing, seated, and inverted postures.

Common Balancing Poses

6. Twisting Poses

Twisting postures are those, in which the spine has revolved around their central axis. It enhances the spine’s natural range of motion and toning up the abdominal organs.

Also, twisting postures are practised in conjunction with intense forward or backward bend to neutralize any blockages (if came in forward or backward bend) in the spine.

Most Common Twisting Poses – Bharadvajasana, Noose Pose (Pasasana), Utthita Parsvakonasana (Revolved Side Angle Pose), Trikonasana (Triangle Pose), etc.

7. Forward Bend Poses

Twisting yoga poses involve rotating the spine around its central axis. These movements enhance the spine’s natural range of motion, stimulate the spinal nerves, and tone the abdominal organs.

Twists are often practised after deep forward or backward bends to help neutralise the spine and release any tension or blockages that may have built up during those movements. They also encourage better digestion and improve overall spinal health.

Common Forward Bend Poses

8. Backbend Poses

Backbend yoga poses are the opposite of forward bends. In these postures, the spine arches backward, creating an opening in the front body while strengthening the back. The arms and/or feet remain grounded, providing stability and support.

These poses help release tension in the shoulders, chest, and upper back. They also improve flexibility in the hip flexors and energise the entire body. Regular practice can enhance posture, boost lung capacity, and open the heart space both physically and energetically.

Common Backbend Poses

9. Inversion Poses

In inversion poses, the head is placed below the heart, which reverses the blood flow towards the head. Some of these poses need strength, balance, and regular practice to master.

Turning the body upside down goes against its usual position, so the benefits are unique and powerful. Headstand, a classic inversion, is often called the “king of all asanas” for its wide range of benefits.

Common Inversion yoga poses

History of yoga poses(asana)

Yoga asanas have evolved and been refined over thousands of years. While modern yogis may effortlessly flow through complex Vinyasa sequences, understanding the roots of these poses is valuable for any sincere practitioner.

The history of yoga asanas can be divided into four main eras:

1. Pre-Vedic Age of Asana

The earliest evidence of yoga postures dates back to around 2500–2400 BCE during the Indus Valley Civilisation.

One of the most notable findings is the Pashupati Nath seal, which shows Lord Shiva (regarded as the God of Yoga) seated in a cross-legged meditation pose, similar to Padmasana.

This seal suggests that the practice of asanas was already an important part of spiritual life long before the Vedic period. It reflects yoga’s deep roots in ancient Indian culture, where postures were used for meditation and self-discipline.

2. Asana in the Vedic Texts

In the yogic context, the word asana first appeared in the fourth Veda, the Atharva Veda (around 1500 BCE). The term comes from the root word aas, meaning “existence”. In this sense, asanas were not just physical poses but a way to develop a stable “state of existence” in the seeker.

In the Bhagavad Gita, part of the Mahabharata, asana is described as “sitting straight” in a comfortable seat. The Mahabharata also mentions two specific asanas Mandukasana (Frog Pose) and Virasana (Hero Pose).

Later, texts like the Visnudharmottara Purana and Brahma Purana (around 300 CE) listed several meditative postures, including Swastikasana, Padmasana, and Ardha Padmasana.

3. Asana in Yogic Texts

Over centuries, great Yoga Gurus in India drew wisdom from the Vedas and Upanishads, compiling it into dedicated yogic scriptures.

Among these, one of the most influential and revered is Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras, composed around the 2nd century BCE.

Asana in patanjali’s yoga sutra

The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali is considered the most complete and systematic treatise on yoga ever written. Yet, while modern yoga often focuses heavily on physical postures, Patanjali devoted only three verses out of 196 to the subject of asana. This means postures form just about 1% of the entire work reminding us that yoga is far more than the poses we practice on the mat.

Patanjali, often called the “Father of Classical Yoga,” defines asana in Chapter 2, Verse 46:

Sthira Sukham Asanam

- Sthira – Steady, stable, grounded

- Sukham – Comfortable, at ease, peaceful

- Asanam – Posture

Interpretation:

When we first enter a pose, it often feels challenging the body resists, and stability takes effort. This is the sthira aspect. With practice, the same posture begins to feel more natural and effortless — the sukham quality emerges. The perfect asana is a union of steadiness and comfort.

In the very next verse, Patanjali explains how this balance is achieved (Chapter 2, Verse 47):

- Prayatna – Effort

- Saithilya – Relaxation

- Ananta – Infinite

- Samapatti – Merging into

- Bhyam – Both

Interpretation

At first, entering a posture requires conscious effort (Prayatna). Gradually, we release unnecessary tension (Śaithilya), allowing the body to settle into its natural state. In this relaxed stability, the mind expands and merges with the infinite (Ananta), and we experience the deeper joy and meditative quality of the asana.

Asana in Hatha Yoga Pradipika

“Asana is the first accessory of hatha yoga which is practised to gain steadiness in pose and lightness in the body” – HYP 1.19

The Hatha Yoga Pradipika (HYP), written in the 15th century, is the oldest known text on Hatha Yoga. While the word Hatha is often interpreted as “something done with force,” the real emphasis in Hatha Yoga is not just on flexibility, but on practising with awareness and discipline.

In this tradition, asana is considered the foundation of Hatha Yoga. Postures are practised not merely for physical strength or suppleness, but to prepare the body and mind for deeper stages of yoga. The text highlights that steadiness and lightness in the body are key goals of asana practice.

4. Modern History of Asana

Most yoga asanas we practise today are fairly recent in history. The modern form of asana started gaining popularity in the early 20th century, led by T. Krishnamacharya, known as the father of modern postural yoga.

His teachings were inspired by Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras and the therapeutic benefits of yoga. He developed sequences of body movements coordinated with breath, now known as vinyasa flow.

Many modern asanas trace their roots to Mysore, where Krishnamacharya trained students who went on to spread yoga worldwide.

Origin of yoga poses

Some yoga postures emerged when India’s traditional exercise system (vyayama) blended with Western gymnastics. These modern yoga asanas are less than 200 years old. In contrast, traditional asanas have roots stretching back over 2,000 years long before Patanjali.

Examples from nature

Many asanas were inspired by observing animals, plants, and natural phenomena:

- Cobra Pose (Bhujangasana): Inspired by the way a cobra lifts its head to release tension and display alertness.

- Tree Pose (Vrikshasana): Modeled after the stability of a tree, encouraging firm grounding through the feet.

- Sun Salutation (Surya Namaskar): A 12-pose sequence performed in reverence to the sun, believed to have ancient origins.

B.K.S. Iyengar explained that in practising asana, yogis transform their bodies into the shapes of animals, objects, or natural forms absorbing their qualities and states of mind.

Yogi while practising asana transforms their body into a specific form of different species or objects. This transformation makes them realise the state of mind in those specific forms. Hence, In asana, we try to hone some consciousness from each type of species or objects.

Why ancient yogis discovered asanas ?

Early yogis found it difficult to sit still for meditation because poor posture caused discomfort, pulling the mind away from focus. Asanas were developed to stabilize and prepare the body, creating a steady seat for long periods of contemplation.

How many yoga asanas are there?

In yoga, it is believed there are 84 classical asanas taught by Lord Shiva, according to several ancient texts. While some scriptures list more than 84, those are generally considered variations of the original classical poses.

Why 84 asanas?

The number 84 is deeply symbolic in yoga and Hindu philosophy.

In Hinduism, it is said there are 8.4 million (84 lakh) species of life on Earth. A soul must pass through these species in the cycle of birth and death before attaining a human birth (manushya yoni). Similarly, a baby in the mother’s womb is believed to pass through 8.4 million subtle forms before being born after nine months.

Applying this to yoga, it is said the muscles, joints, and body parts can move in countless ways. Lord Shiva gave 8.4 million possible movements, but to make them practical for human life, one pose was chosen for every 100,000 species.

That’s how we get the 84 classical asanas:

8,400,000÷100,000=84

The number of asanas according to the various famous yogic text is the following:

1. According to Yoga Sutra

Number of Asana – Not Defined

Author – Patanjali

Found in – 2nd Century BCE

Patanjali, the father of yoga, didn’t mention the name of any asana in his famous book ‘Yoga Sutra’. Indeed, yoga sutra comprises three asana verses in chapter 2, which elaborates the necessary element of a correct seated posture.

Later on, commentary on Yoga Sutra by Bhasya suggested 12 seated yoga posture for meditation practice.

- Padmasana – Lotus Pose

- Virasana– Hero Pose

- Bhadrasana / Baddha Konasana – Gracious Pose

- Svastikasana– Auspicious or Cross Pose

- Dandasana– Staff or Base Pose

- Sopasrayasana – Supported Pose

- Paryankasana – Couch Pose or Bed Pose

- Krauncha-nishadasana – Seated Heron Pose

- Hastanishadasana – Seated Elephant Pose

- Ushtranishadasana – Seated Camel Pose

- Samasansthanasana – Evenly Balanced Pose

- Sthirasukhasana – Any motionless posture that is following one’s pleasure ?

2. According to Goraksha Samhitha/Goraksha Paddhathi

Number of Asana – 2

Author – Gorakshanatha

Found in – 11th Century

An early Hatha yogic text, Goraksha Samhita, stated 84 types of asanas. These 84 asanas are considered to be extracted from the original 8.4 million (84 Lakh) asanas. Out of 84 stated asanas, Goraksha Samhita describes only two meditative sitting postures in detail.

3. According to Shiva Samhitha

Number of Asana – 4

Author – Unknown

Found in – 15th Century

Shiva Samhitha stated 84 asanas along with Prana, mudras, and siddhis (powers). Further description of the following 4 sitting asanas is there in Shiva Samhitha.

- Siddhasana – Accomplished Pose

- Padmasana – Lotus Pose

- Ugrasana – Stern Pose

- Svastikasana – Cross Pose

4. According to HYP

Number of Asana – 15

Author – Swami Svatmarama Suri

Found in – 15th Century

One among three most influential texts on hatha yoga (Other 2 being Gheranda Samhita and Shiva Samhita), HYP has described 15 asanas out of 84 in detail.

- Swastika asana – Auspicious Pose

- Gomuka asana – Cow Face Pose

- Virasana – Hero Pose

- Kurma asana – Tortoise Pose

- Kukkuta asana* – Rooster Pose

- Utttana Kurma asana – Upside-Down Tortoise Pose

- Dhanurasana* – Bow Pose

- Matsyasana – Fish Pose

- Paschimottanasana – Seated Forward Bend

- Mayurasana* – Peacock Pose

- Savasana* – Corpse Pose

- Siddha asana – Accomplished Pose

- Padma asana – Lotus Pose

- Simha asana – Lion Pose

- Bhadra asana – Gracious Pose

Further, out of 15 above asanas described in HYP, 11 asanas are only sitting postures for practice meditation (asanas without the asterisk).

5. According to Gheranda Samhita

Number of Asana – 32

Author – Gheranda

Found in – 17th Century

Out of 84 preeminent asanas, Gheranda described 32 asanas which are said to ‘useful in the world of mortals’. Some out of these 32 asanas have already described in HYP.

6. According to Hatha Ratnavali

Number of Asana – 84

Author – Srinivasa

Found in – 17th Century

Yogi Srinivasa has made first attempt to list all the 84 asanas in Hatha Ratnavali. Although the name of all 84 asanas is provided in his text, only 52 out of 84 described by the text itself.

7. According to Joga Pradipika

Number of Asana – 84

Author – Ramanandi Jayatarama

In – 1737

In Joga Pradipika, 84 asanas illustrated in painting form rather than any verbal description. With Joga Pradipika, it came to know the first time that most of the asanas among 84 asanas are sitting postures and practised to bring therapeutic benefits.

8. According to Light on Yoga

Number of Asana – 200

Author – B.K.S Iyengar (Guru Ji)

In – 1966

Founder of Iyengar yoga style, Guru Ji has demonstrated 200 asanas with his 600 monochromes photographs in his book “Light on Yoga“. These asanas have categorised into a grading system of 1 to 60 based on difficulty. ‘Light on Yoga’ also known as ‘bible’ of yoga, as asanas were never demonstrated in this descriptive way before.

9. According to Master Yoga Chart

Number of Asana – 908

Author – Dharma Mittra

Founded in – 1984

Master yoga chart comprises 908 yoga asana devoted by Sri Dharma Mittra to his Guru Yogi Gupta. This chart is usually hung around different yoga studios around the world to help the teachers and students in asana practice.

Benefits of yoga asana

Asanas are a core part of yoga that help improve both physical and mental health, enhancing overall quality of life. Whether it’s physical issues like back pain, muscle stiffness, and joint discomfort, or mental challenges such as anxiety and depression, regular asana practice can support recovery and well-being.

Here are some evidence-based benefits of practising yoga asanas:

1. Promotes muscles and joints flexibility

Standing yoga poses like Mountain Pose and Half Moon Pose are known to improve joint movement and muscle flexibility. Better flexibility helps prevent aches and stiffness in the joints.

Regular asana practice also protects against conditions such as arthritis, osteoporosis, and back pain. This is because yoga involves moving the joints and muscles through their full range of motion, keeping them healthy and strong.

2. Improves respiratory system

Yoga asanas combined with deep, mindful breathing are excellent for strengthening the lungs. When you practise sitting asanas with controlled breathing, the lungs become more elastic and function better.

Sitting and supine yoga poses with yogic breathing are especially helpful for people with asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). These practices help improve both the capacity and flexibility of the lungs, making breathing easier and more efficient.

2. Reliefs from stress and anxiety

Yoga asanas help relax the body by holding it in specific positions. When we relax, deep and focused breathing fills our lungs with fresh oxygen. As we stretch or bend in a pose, this oxygen circulates quickly through the body, nourishing the internal organs. This process also helps calm the adrenal glands, reducing stress.

A pilot study found that practising asanas can increase brain GABA levels. Higher GABA levels are linked to reduced symptoms of depression and anxiety.

Some of the best asanas for stress and anxiety relief include Savasana (Corpse Pose) and Balasana (Child’s Pose).

3. Improves Physical balance

Asanas are all about the body’s position and alignment. Some are practised standing, others sitting, and some lying down.

When holding an asana, practitioners often focus their gaze on a single point while maintaining the same posture for an extended time. This steady concentration, combined with the physical effort of holding the pose, helps improve the body’s balance and stability.

4. Brings equanimity of mind & body

The human mind is often restless, swinging like a pendulum between the past, present, and future, and between sorrow and happiness. This instability can give rise to fear, anxiety, and anger.

While practising asanas, the mind focuses on the present posture rather than wandering to the past or future. This steady focus aligns the mind with the body, creating a sense of balance and calm in both

Yoga Asanas FAQs

Answer: As we know yoga poses are mainly emphasized on the body, rather than the mind and other psychological aspects. Ancient yogis placed asanas before pranayama and meditation (mind practices) so one can master their body first and then understanding the mind become way simpler.

Answer: Common contraindications for yoga poses are, asthma, back injury, diarrhea, high blood pressure, menstruation, pregnancy, and shoulder injury. However, you can always practice poses with some modifications under the guidance of an expert teacher.

Answer: A good yoga sequence of poses starts with sitting (meditative) posture, then warm-up stretch, standing postures, few arm balancing, inversions, core strengthening poses, backbend, shoulder stand, forward bend, and finally end the session by relaxing in corpse pose.

Answer: It totally depends on how much time you can devote to your practice. If you haven’t much time, do 4 rounds of the sun salutation as it involves almost all body parts. In Ideal conditions, a session should comprise 13-15 yoga poses in the manner described above (comprises all types of yoga poses). Each yoga pose can be held for an average duration of 3-5 minutes, which makes a session around 1 hour long.